From the readings, what are the ethical, social, and moral issues regarding online censorship? Why would governments limit freedom of speech and how do they go about enforcing these restrictions? Is it ethical or moral for technology companies to follow requests of the host country to suppress freedom of expression? That is, should technology companies comply with censorship requirements of the country they are operating in? Is it ethical or moral for technology companies or developers to provide tools that illegally circumvent such restrictions? Is online censorship a major concern? What role should technology companies play in defending against of enforcing limitations of freedom of speech?

Censorship seems straightforward enough as an ethical issue—censorship is bad, period—but upon further thought it’s more complex and layered than it seems. Because everything that’s uploaded to the internet is practically permanently public, let’s consider the following questions as we unpack the concept of “censorship”:

- Is it ethical for companies to remove dissenting opinions for authoritarian governments?

- Is it ethical for companies to remove information broadcasted by terrorism organizations, or about terrorism organizations?

- Is it ethical for companies to remove discriminatory, provocative, hateful content generated by its users? (read: reddit)

- Is it ethical for companies to remove leaked/stolen personal photos? (read: celebrity nudes on 4chan)

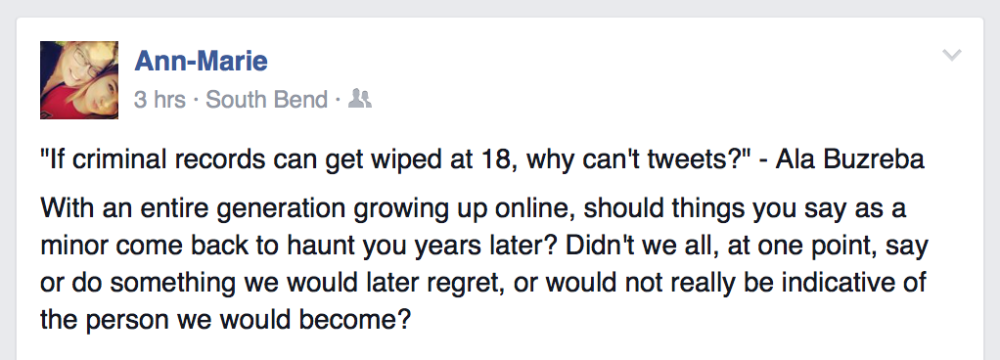

- Is it ethical for companies to remove smearing and slander against an individual? Is “the right to be forgotten” ethical?

- Is it ethical for criminals to claim the right to be forgotten?

Putting these scenarios together, I find the line incredibly difficult to draw. Even if we only consider the situation with terrorism, since the list of terrorist organizations are decided by governments, companies are essentially performing censorship at the request of governments. In situations like Tibet—China considers some Tibetan Buddhist groups terrorism organizations (because of their use of self-immolation), while the U.S. recognizes them as legitimate religious groups—how do we choose?

I want to close with a more personal, intimate scenario. Here’s a question posed by a Notre Dame professor, and I’ve been thinking about it for a while without getting to a conclusion. We’ve all posted things that we later regret—is “regret” a good reason to remove anything from the internet? When things are published on the Internet, who owns them?